We are back home in the Land of Enchantment after ten epic days in the east, mostly in New York City, but with a few visits to my old stomping grounds in New Jersey, across the bay.

I was able to enjoy Thanksgiving with my sisters Darleen and Janet and my various nieces, nephews, grand-nephew, and a couple of new-born grand-nieces. First time in more than a decade that I’ve been able to spend the holiday with family, so that was very special. We were able to enjoy some Broadway shows and even a Giants game (the G-Men won, wonder of wonders), and of course I saw my various agents and editors and publishers, many of whom are based in the city.

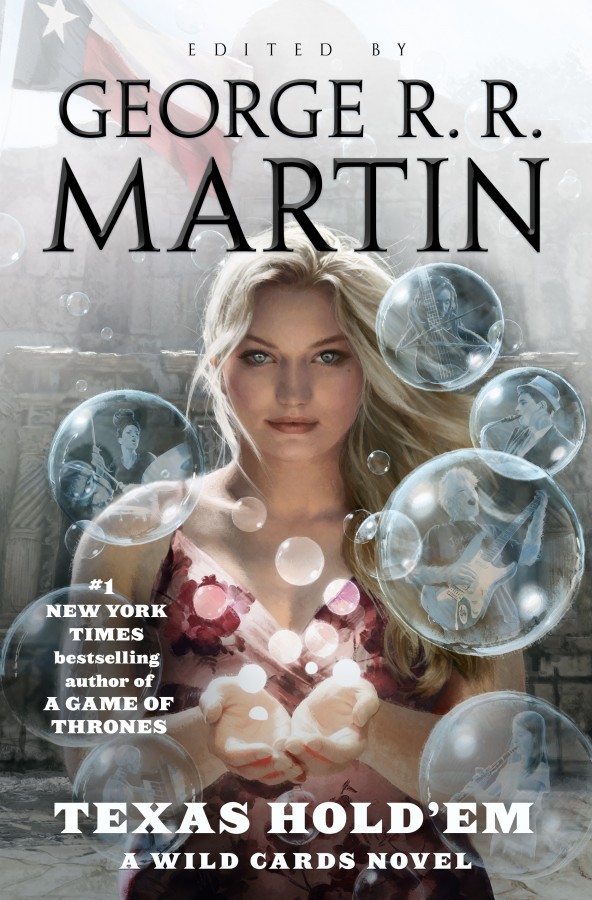

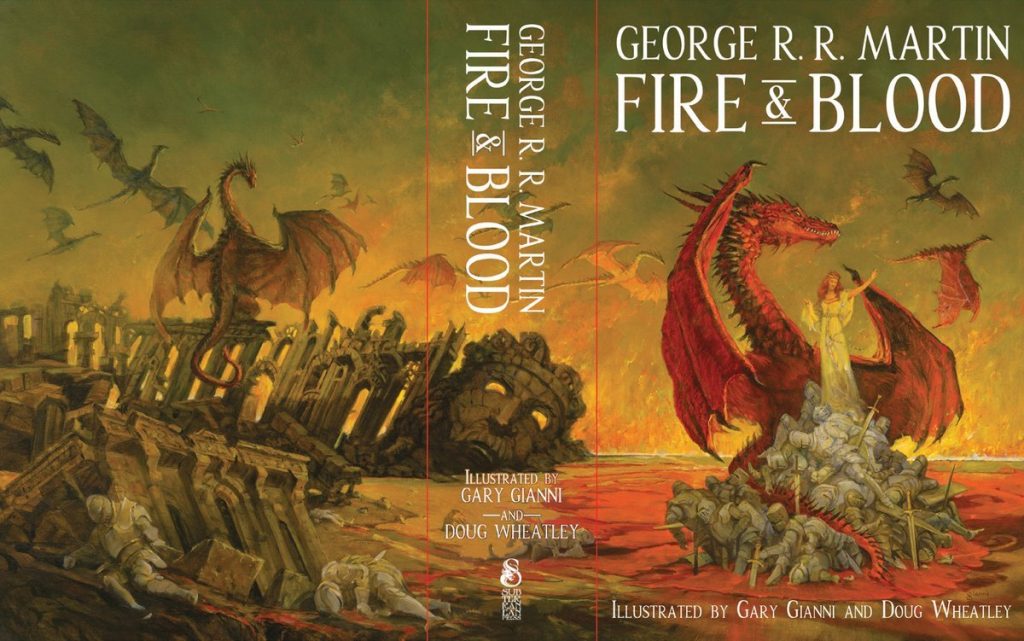

It wasn’t all pleasure, though. Most of the trip was business: the long-planned launch of my new Westeros book, FIRE & BLOOD.

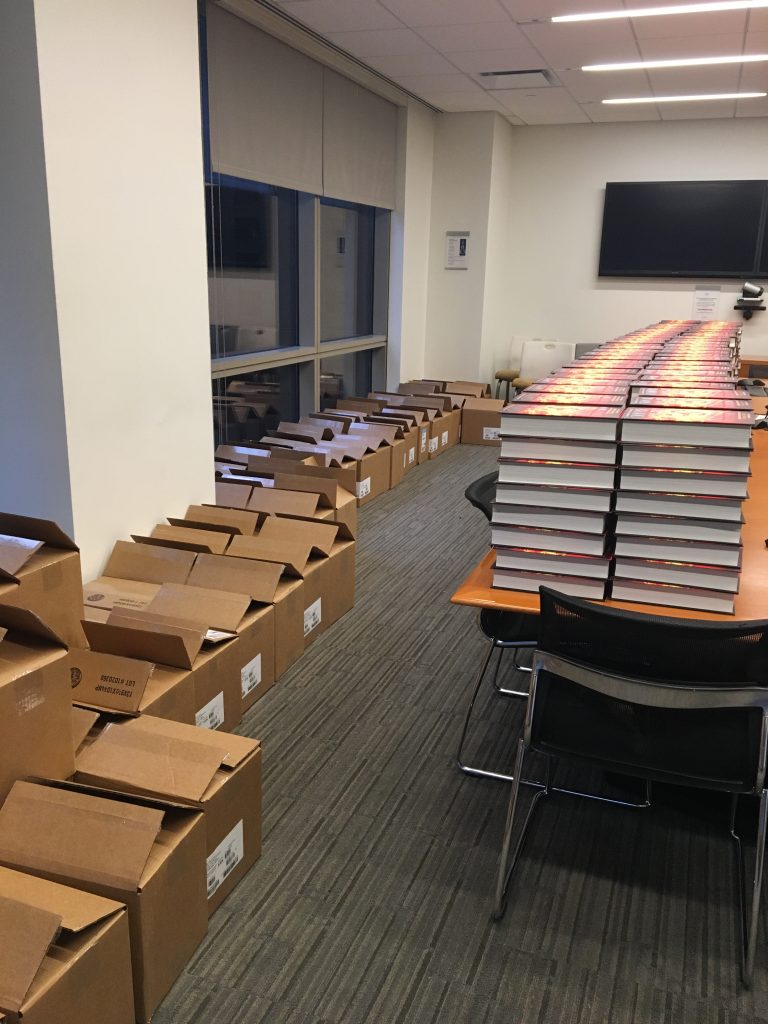

I had barely gotten off the plane when I had to report to Random House to sign (ahem) “a few copies.”

a few copies

“A few” in this case translates to 1600 copies, all earmarked for the official FIRE & BLOOD launch on November 19 at Loew’s Jersey, an enormous 1930s movie palace in Journal Square, Jersey City. I spent many a Saturday afternoon at Loew’s (and the other great movie palaces in Journal Square, the State and the Stanley), when I was a kid growing up in Bayonne. It’s a magnificent theatre, a real treasure… and it came within a hair’s breath of being torn down a few years ago, before a group of cinema lovers and preservationists called the Friends of the Loew’s stepped in to save it. Being featured on the marquee of this amazing theatre where once I saw films like BEN-HUR and LAWRENCE OF ARABIA was a real joy for me.

The evening was a HUGE amount of fun, in no small part thanks to my friend John Hodgman, who hosted the event and conducted the interview. If you weren’t able to get into Loew’s, you can find the entire thing on the net:

(The organ was amazing as well. Another cool thing about the Loew’s).

The crowd was wonderful, the theatre was beautiful, John was a delight; all in all, it was a great evening, and the perfect way to introduce FIRE & BLOOD to the world.

It was not my only event, however. The next night, I appeared on THE LATE SHOW with Stephen Colbert (inside another historic theatre, the Ed Sullivan, the same stage where Elvis, the Beatles, and Topo Gigio once trod). Stephen and I have a lot in common: we’ve both Northwestern alums and comic book fans, and he loves Tolkien even more than I do. We could have talked for hours, but we had only a few minutes:

New York is indeed a helluva town, like the song says. It’s always good to come back for a visit, and this trip was especially satisfying. My thanks to all those who helped make it special: John Hodgman, Stephen Colbert and his producers, Anne Groell, Scott Shannon, David Moench and my wonderful team at Random House, my agents Kay McCauley and Chris Lotts, my fearless minions Lenore and Sid, my family… and of course, Parris.

I hope all of you reading this had a great Turkey Day. Gobble gobble.

(FIRE & BLOOD is now available from your favorite local bookshop or online bookseller. If you want a signed copy and missed the Loew’s event, however, you can place a mail order with the Jean Cocteau Cinema).

Current Mood:  cheerful

cheerful

melancholy

melancholy

null

null

pleased

pleased

busy

busy awake

awake

excited

excited

bouncy

bouncy contemplative

contemplative