|

The Usual

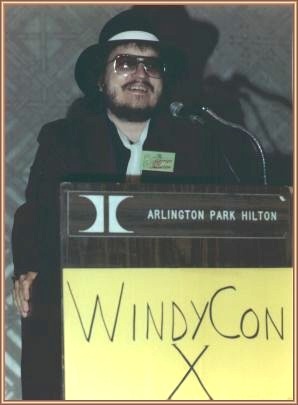

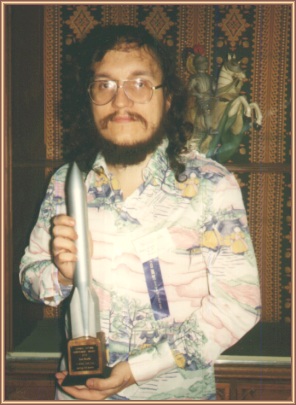

I haven’t been a convention Guest of Honor as often as some writers in our field, but I’ve been there often enough to know one thing for sure – I like it. It’s always nice to be a GOH, for all the obvious reasons; I think it’s in the rules somewhere that the GOH gets to have more fun than anybody else, and even when it’s bad, it’s great. Nonetheless, I have to admit that I’m particularly pleased to be here this weekend, at Windycon, because as many of you know — a lot of my roots are here in Chicago. It’s true. I went to school up at Northwestern, as some of you may know, and I lived in Chicago itself from 1971 through 1976, in Uptown. I have lots of memories of Uptown. I don’t know what the neighborhood is like thse days, but ten years ago it was what I liked to call “yeasty.” It was as mixed a neighborhood as I’ve ever seen or heard of; ethnically, racially, economically, chronologically. Topless bars and old folks’ homes and condos were within a couple of blocks of each other. Upwardly mobile young singles and leftover hippies and lots of muggers and killers all milled around together, sometimes even in my apartment. A different ethnic group moved in every week. I have lots of memories of my years in Uptown. I remember this sort of grocery store-cum-deli that I used to stop at on the way home from work. I’d pick up some pastrami, some roast beef, maybe a barbequed chicken. They had racks of barbequed chicken turning in the windows. It was run by these two old Jewish men, and the food was pretty good, and I shopped there regularly. Then one day it changed. I came in and the two old Jewish men were gone, and instead there was a woman in a sari behind the cash register, and a dark, swarthy man behind the deli counter. They still had the chickens turning in the window, though, so I figured what the hell, I went on over, and ordered a pound of roast beef. But the counterman had just started to take out the roast beef when I changed my mind. “No,” I said, “I think I’ll have some pastrami instead.” He looked at me blankly. “Pastrami,” I repeated, and the incomprehension grew in his eyes. He didn’t speak English very well, you see. Well, I tried to spy the pastrami behind the glass and point at it, but it wasn’t there. “Maybe you don’t have it any more,” I said. “Pastrami? You know, little bit like corned beef?” But he wasn’t getting any of it. I was reduced to making slicing motions and — in the timeless tradition of American travelers everywhere — repeating myself more loudly. “Pastrami,” I kept saying. “Pastrami, pastrami.” Finally he seemed to get what I was saying, and a big smile broke over his face. “No, no,” he said, pointing at his chest. “Pakistani!” That was what life was like in Uptown. I didn’t mind. It seemed kind of an appropriate place for a struggling young neopro. I had a huge old apartment that had known much better days, but was still great for parties; I shared the place with an endless array of roommates, a half-dozen cats, and several thousand roaches. Every morning I walked to this place called Don’s Grill for breakfast. Ah, yes, I remember Don’s. It was about the greasiest spoon you could imagine, but still a good place for breakfast. For a buck-thirty-one you got two eggs and bacon and lots of hash browns and all the coffee you could drink and any kind of toast you wanted — I usually wanted cinnamon raisin toast — and they’d even throw some onions into the eggs for nothing. The waitresses were named Flo and Vi, I swear to god! It was the only restaurant in the world where I’ve ever managed to achieve what has been one of my lifelong ambitions: to be able to go in and sit down and tell the waitress, “Give me the usual.” My ambitions were modest in those days, but then, so were my means. Windycons were as much a part of those days as was Don’s, though not, thank god on a daily basis. I haven’t managed to make a Windycon since I moved down to the wilds of New Mexico, but in earlier years I was a regular, more or less. I attended the first three, back in the prehistoric days when they actually held the con in Chicago, plus a couple of the later ones out here at Arlington Park. I got my first Hugo at a Windycon, in fact. This may strike you as a trifle odd, the Hugo Awards banquet not being a regular feature of Windycon programming, but it’s true. The thing was that year the worldcon was in Australia. I had barely enough money to buy breakfast every morning at Don’s, so I knew there was no way I was gonna swing any Australian coffee shops. So I wasn’t there when they announced that I’d won; I was at home my apartment in Uptown, asleep, in my underwear, and somebody from Western Union phoned at an ungodly hour of the ayem with a telegram from Neal Rest telling me that I won. I said, “Huh, yeah,” and went back to sleep, and the next morning I was half convinced it’d all been a dream. But it was real enough, and Ben Bova picked up my Hugo for me. He brought it to Minnesota, where he stopped on the way back from Aussiecon, and gave it to Gordy Dickson. Gordy kept it for a while and passed it to Joe Haldeman when he came through. Joe didn’t have one of his own yet — this was before he got greedy and won six or nine or however many he has now — so he used mine for all the unspeakable rituals he’d always wanted a Hugo for, and brought it to Windycon, where he gave it to Lynne Aronson, the founder and chairman of this institution, although it was smaller and less institutional in those days. Lynne presented it to me at the (ahem) banquet. If you could call it that. Actually, it was an all-you-could-eat breakfast buffet, which meant I had to get up in the morning, on Sunday, after the Saturday night parties. But I was ready to do anything to get that Hugo. I’d been making do with an old chess trophy covered with aluminum foil, but it wasn’t the same thing.

Anyway, that was in my callow youth, when I was only a struggling neopro. Now I’m back, this time as Guest of Honor. I mentioned how much I like being a Guest of Honor, I believe. I’m hopelessly addicted to cons by this point, and being a Guest of Honor means I get to go to one for free. Besides, things are a lot different when you’re a Guest of Honor; there are all kinds of fringe benefits I never dreamed of when I was a struggling young neopro. When I was struggling young neopro, I had to ride the el to get to Windycon; as Guest of Honor, I get to ride Pioneer Airlines. As a struggling young neopro, I often had to sleep on people’s floors at cons; when you’re Guest of Honor, they give you a room. As a struggling young neopro, you have to go to the con suite to get a beer from the bathtub; when you’re Guest of Honor, you drink the same beer, but if you’re lucky a gopher will get it for you. Sometimes, when you’re Guest of Honor, the hucksters will even stock your books. If you’re really lucky, sometimes people will even buy some of them. Of course, there are disadvantages to being Guest of Honor. The biggest one is that they make you give a speech. Sometimes they make you go to a banquet in order to give a speech, although at least you’re assured of getting a sweet roll when you’re Guest of Honor. Now I haven’t been Guest of Honor a whole lot in my career, but I’ve been there enough so I’m starting to run out of topics. I talked about the state of the field in my first two, and then about editors, and then about reviewers, and then about turtles, which seemed like a logical progression at the time. Anyway I don’t want to repeat myself. So this time I decided I’d talk about fandom. I could talk about how fandom is my family, but you’ve all heard that and it’s boring and besides, I’d be up shit creek if my family found out. They had enough trouble when I had a panel discussion and GOH speeches at my wedding, they’d never go for the people in antlers and beanies. Well, I tried all these topics on for size, and none of them really fit, but the obvious choice was there all along, pushing its way into my thoughts. This weekend represents a kind of homecoming for me. Until Bayonne, New Jersey becomes a fannish hotbed and establishes its own annual convention, or until my high school reunion heaves around — a thought that chills me to my bones — it’s about as significant a homecoming as I’m likely to get. Chicago represents a large chunk of my past, and having been asked back here, it’s impossible not to reflect on where I came from and where I am now and how things have changed. On how things have changed for all of us. I’ve changed, certainly, since that weekend ten years ago that I spent partying at the Blackstone. In obvious ways — moved four times, got married and divorced, made some friends and lost touch with others. I learned to cook my own breakfast, and when I’m in the mood, I can now afford restaurants that are a bit classier than Don’s Grill — although I’ve never found another place where I can just sit down and order my usual. The funny thing is, I find that a little sad. In one of those little ironies of timing that sometimes seems inevitable, I have a new book coming out next month, a novel called The Armageddon Rag that is, in fact, about change and loss and some of the things I’m groping around for up here. I say it all a lot better in the novel, I think. The Rag is about rock ‘n roll, and it’s about the Sixties, and the Eighties, and the things we’ve gained and lost along the way. It has elements of a mystery novel, and elements of occult horror, and elements of mainstream too, I guess. It’s about the changes we wanted and the changes we got, which weren’t the same thing at all. It’s a symbol of my own personal changes as well, since it is utterly unlike anything I’ve done before. I’m pleased with that, incidentally. I think the work has to change, that a writer who repeats himself too often is on the road toward stagnation and self-parody. All writers repeat themselves to a certain extent, of course; themes recur, a distinctive voice develops, characteristic concerns and literary motifs become discernible. But you have to keep trying new things, if you’re to be worth reading at all. That’s one of the things that worries me most about today’s SF. So many writers seem to have stopped trying new things. I’m not even talking about the wildly experimental, mind you — for a writer who’s done nothing but sword & sorcery, a space opera is a wildly new thing, on a personal level. Too many editors seem intent in keeping us in our pigeonholes — both SF as a whole, and individual SF writers. I love SF enough to hope rather fervently that this is just a phase we’re going through, that the diversity I’ve always valued in our field will return. And I think it will. Those of you who are paying close attention may have noticed contradiction here: here I am, all in favor of change, somewhat wistfully rueing what SF has gone and changed into. I plead guilty to that, to having an ambivalent attitude toward change. But I don’t think that’s terribly unusual in the world of science fiction. For all of our claims extolling our chosen literature as an antidote to future shock, we’re as much in love with our yesterdays as with our tomorrows. The same people who will sit up on panels and talk about how five years from now we’ll all be living in bio-engineered houses grown from mushrooms, with nuclear fusion furnaces, and commuting to work via hang gliders — the same people who will seem eager for all this to come to pass — will react with horror if someone suggests changing the Hugo rules. The guy who tells you that there is going to be an inevitable nuclear holocaust come 1986 is also on a bidding committee for 1987. Perhaps I ought to decry that, but I can’t, won’t. I see too much of it in myself. And it’s something I value in SF and the SF people I’ve come to know and love. I remember those years in Chicago, a decade ago. I was a great one for throwing parties in those days; my apartment was perfect for it, and I had a streak of sadism that enjoyed making my friends come to Uptown. My parties were very diverse. I’d gone to Northwestern, as I’d mentioned; I’d been extremely active in college chess there, serving as president of the campus club and captain of our intercollegiate teams. Naturally, I had a lot of old college friends, most of them chess players, and they came to my parties. From 1972 through 1974, I was working as a C.O. attached to VISTA and the Cook County Legal Assistance Foundation, so I also knew a lot of radical young lawyers and VISTA volunteers. They came to my parties. And, finally, I had my writer friends, my friends in fandom. They came too. Everyone came crowding in to my big Chicago apartment and a couple of the better parties ran till dawn. But it was like mixing water and oil and mercury. The chess players all brought sets and clocks and they sat on the floor in my dining room and played speed chess. The lawyers took over the living room, turned the lights down and the stereo up, danced and smoked pot. The SF people all went off and sat around and talked. There were friends that I loved and cared about in all three groups. In fact, if you’d cornered me then, back in 1973, and put me on the spot, I probably would have said I was closest to the chess people, the college friends I’d known the longest. And the runners up would be those lawyers I worked with every day. The SF people –well, I was new to SF, and the relationships there were newer, more tentative. But now a decade has passed. I still write to one or two of my college chess player buddies, and I look ’em up if I visit whatever city they might be living in, but that’s about it. Most of the Legal Aid folks I’ve lost touch with entirely. But the SF people are still a big part of my life. Bigger than ever. They write and they phone and they get together at these cons a staggering number of times each year, and the result is a kind of floating permanence. In a world where everything is changing, where people hop from city to city and leave their life behind them when they go, where friendships and love affairs and marriages all seem more transitory every year, the SF subculture has created a kind of island of permanence. Out in the larger world, your buddy or your lover may very well turn into a name on your Xmas card list within five years but here, your friends and your enemies are going to be a part of your life forever, whether you want them to or not. In the name of what is sometimes called the literature of change, we have created a world where nothing changes, where the con schedule is a regular as the seasons. I think that’s good. Almost from the first, I’ve been addicted to this world, to these conventions. For a long time I didn’t know why. I knew from the start that it wasn’t the ‘fans are slans’ shit. Fans are no smarter or more hip than anybody else. Some of those chess players I knew were brighter by far than most SF people; the lawyers dressed better, were more socially adept, were a good deal less naive about politics. No, I figured out early that fans and mundanes, down deep, were much the same. As a group, we’re about as diverse as James Watts’ coal committee. It wasn’t the talk about SF that drew me either, or the hot crowded parties, or the beer, too often warm, piled up in the bathtubs. I think, all along, that I sensed the permanence to be found here. In an interview I did recently, the interviewer noted that my work has undergone a definite transition over the years. In the beginning, I was writing a sort of romantic variety of SF, with plenty of spaceships and aliens, traditional enough so that some people called me an Analog writer. Later on, I fooled around with science fiction horror hybrids, and then a few contemporary horror stories in the King vein, and then historical horror in Fevre Dream, and now Armageddon Rag, whatever it might be. I’m not entirely sure of that either. Mainstream-mystery-fantasy, I think. You figure out a better label, come tell me. Anyway, the interviewer asked me if I’d left SF. I didn’t know how to answer. If I’ve left SF, I certainly wasn’t conscious of it at the time, but looking back it certainly seems as though I’ve at least drifted away from the center of the field. And where am I going next? Hell, I’m the wrong one to ask; I don’t have the foggiest. I have a good number of SF ideas I want to write to write someday, stories as full of stars and spaceships as anyone could possibly desire. I also have historicals I want to write, and contemporary novels, and odd hybrids. My next novel, I think, is going to be about a grand old 30s movie palace where strange things happen. After that, who knows? I would hope that the next ten years will see fully as many changes in me and my writing as the last ten have seen. But I know this: regardless of where my writing may take me, or how my reading may wander, I’m an SF person and I always will be. I’ve got too many ties here to ever leave this world. I’ll be going to worldcons until I die, and the chances are good I’ll be showing up at future Windycons from time to time as well. They are all homecomings, these cons of ours — homecomings that give a continuity to our lives, that keep our past a part of us. In a world where the changes are not always the ones we’d wanted, and where even the best of changes carries with it a loss, these conventions are a place where we can walk up to the registration desk and say, “Give me the usual,” and they’ll know — with a certainty — who we are, and what we want. |

Guest of Honor Speech

Guest of Honor Speech That breakfast was absolutely interminable. Not only was the food bad, but there wasn’t enough of it — far from being all you could eat, they ran out before everyone had been served. Then we waited and waited before they brought more dead scrambled eggs. But the real swell touch was the tables. Every table had seating for eight, and in the middle of each, as we filed in, was a plate piled high with sweet rolls. Six sweet rolls, to be precise. Wonderful fun. That was a hotel with a sense of humor, that was. I did get a Hugo that morning, finally and I got a sweet roll too. I don’t know which was the grander accomplishment. They were about equally sticky, although the Hugo had more fingerprints on it.

That breakfast was absolutely interminable. Not only was the food bad, but there wasn’t enough of it — far from being all you could eat, they ran out before everyone had been served. Then we waited and waited before they brought more dead scrambled eggs. But the real swell touch was the tables. Every table had seating for eight, and in the middle of each, as we filed in, was a plate piled high with sweet rolls. Six sweet rolls, to be precise. Wonderful fun. That was a hotel with a sense of humor, that was. I did get a Hugo that morning, finally and I got a sweet roll too. I don’t know which was the grander accomplishment. They were about equally sticky, although the Hugo had more fingerprints on it.